What is MEV?

MEV stands for Miner/Maximal extractable value, and it is a measure of the profit a miner (or validator or bot) stands to make through their ability to include, exclude and re-order transactions within the blocks they produce. Since Jan 1st, 2020, the cumulative extracted MEV is $908.3 million, with $130.3 million being extracted in the last 30 days.

This estimate of cumulative MEV extracted, however, is just the tip of the iceberg. It represents the MEV that has both been detected and extracted and as such represents a lower bound estimate. It would be an impossible task to calculate a blockchain’s total potential MEV as every time a user interacts with the blockchain or the functionally infinite smart contracts on the chain, MEV can be created. Below I have created a visualisation of what this may look like using Ethereum’s lower bound MEV. Our cumulative MEV estimate for Ethereum therefore misses out on the MEV that has been extracted but we haven’t been able to detect and the MEV that bots were not able to extract, but theoretically it is possible. We shall talk a bit about the future state of MEV later and how I expect we will gradually start to eat into that missed MEV section. But lets now look into what MEV actually is and how it works.

To do this, we first need to revisit some blockchain fundamental. Let’s take a simple example.

Let’s say Bob wants to some send ETH to Joe. He copies Joe’s Ethereum address and clicks send. But what happens now?

1. By clicking send Bob has signed his transaction and is it sent to the node he is connected to.

2. This node then communicates with the other nodes in the network and Bob’s transaction is placed in the Mempool.

3. The Mempool is all the cryptographically verified transactions (when Bob signed transaction with private keys) that are unconfirmed/ pending. These transactions haven’t been mined yet and so are not part of the blockchain.

4. The miner’s job is to take the pending transactions in the Mempool and order them to into a block. They then need to guess the correct hash in order to mine the block and share it with the other nodes before adding it to the chain. Once the transaction is placed in a block and mined, Joe gets his ETH.

It is the ordering of these transactions by miners that allows MEV to occur. The miners choose the order of transactions based on their incentive to make the greatest profit. This most commonly was the amount of gas paid to process a transaction. The higher the gas fee, the higher the transaction is ordered in the block. MEV now represents another profit incentive for transaction ordering, as miners can earn profit by exploiting front-running opportunities or arbitrage trades.

Types of MEV

The most common types of MEV are front-running, back-running and sandwich attack extractions, however, there are more serious types of MEV that pose a large threat to the consensus of blockchains called Time bandit attacks. We will get to this later.

Front running

Front running extraction is where a bot sees a transaction sitting in the Mempool and front-runs the transaction by paying a slightly higher gas fee to move ahead of it. The bot would therefore be able to execute a buy or sell before the user and in many cases the user’s transaction will fail or execute at a worse price.

Back Running

The second type of MEV is back running. This is when a bot detects a transaction in the Mempool that will likely cause a large dislocation of price due to slippage. The bot will execute an arbitrage transaction directly after to bring this assets price back to parity. This type of MEV is Benign MEV as it helps make the market become more efficient.

Sandwich Attack

Next, we have Sandwich attacks. A Sandwich attack is when a bot places a buy order in front of a user’s transaction and a sell order directly after the user’s transaction. The example below shows how a bot recognised the 8.86 ETH buy order in the Mempool and placed a 1.69 ETH buy order directly before it. The user’s order is then executed at a higher price and the bot then immediately sells into this price, making off with a 0.17 ETH risk free profit. Unlike back-running, Sandwich attacks are classified as malignant MEV. This type of MEV causes harm to the user as their order is executed at a worse price and it is akin to levying a tax on the user.

You may have noticed these bots in the order books of dexscreener.com. You can check if you have ever been victim to a sandwich attack here: sandwiched.wtf

History & current state of MEV

The history and current state of MEV can be defined by non-miner activity. Ethereum miners are not yet attempting to exploit MEV by arbitrarily ordering blocks or censoring transactions and it is the arbitrage bots running on DEXes that account for most of the extracted value. In fact, arbitrage (including sandwich attacks) accounts for 99.46% of the total MEV extracted on Ethereum, with the vast majority of occurring on the Uniswap V2 exchange (64%).

Looking at the history of MEV, starting in January of 2020, we can see that the space was dominated by ‘Priority gas auctions’ (PGA). MEV bots would both identify an MEV opportunity in the Mempool and enter a bidding war to extract this MEV. The bot with the highest gas bid would have their transaction included in the block by a miner, winning the MEV opportunity. This state of play created negative externalities at the network level as it led to high gas prices across the network and frequent reverted transactions. Since Jan 1st 2020, the total wasted fees on failed MEV transactions due to reverts comes in at $12.8 million, which, assuming a total block of gas is 12.5 million, implies 6,253 Ethereum blocks have been wasted. Not a great sight when you consider the average user has already been priced out of the network due to the excessive fees.

The current state of play however has greatly reduced these negative externalities as the bidding process is now done via Flashbots private channels. This means the typical PGA and failed transaction reverts are becoming less common. MEV bots now create a bundle of transactions and submit a private bid to the Flashbots channel, the miner then chooses bundles to include in their next block based on the payment per unit gas. This reduces the negative externalities at the network level but currently it does little to prevent them at the user level, as users are still being front-run and sandwich attacked.

The Future of MEV

Since the current state of MEV is dominated by non-miner arb bots, the MEV that is extracted is classified as ‘simple’ MEV. However, since miners can order the transactions in blocks and censor transactions, they are able to extract more complex forms of MEV. I won’t touch on all of them here, but I would like to talk about the so called ‘Time Bandit’ attacks and how with the growth of DeFi, they pose an existential threat to Ethereum.

Named after a 1981 Fantasy film all about the “craziness of our awkwardly ordered society and the desire to escape it through whatever means possible”, the Time Bandit attack is just that, the desire to escape the preordained blockchain and to ‘go back in time’ to reorganise past blocks and extract the MEV in these blocks.

To explain this phenomenon, let’s walk through a simple example involving two miners, George and Jane. Each block mined generates a $100 block reward to the miner and in each of the block there is the potential to extract MEV, usually an order of magnitude larger than the block reward. Let’s just say each block has $1,000 MEV.

1. Jane has mined two blocks (4 & 5), at this point George can continue to mine on top of Jane’s blocks or he can attempt to re-mine blocks 4 & 5 and capture the MEV in each of those blocks for himself.

2. Since the reward is great enough, George has the incentive to re-mine blocks 4 & 5 and alter the transactions in them to capture this $2,000 in MEV for himself.

3. This ‘splits’ the network and is akin to a 51% attack on the chain.

4. George has now mined 4 & 5 and captured the MEV, he now owns the longest chain and he and Jane can progress on mining the 6th block.

This reorganisation of blocks would not just effect Jane, it could mean an average users’ transaction that was once confirmed has disappeared and may or may not be included in the preceding block. The consensus of the network would be questioned and you could never be sure if your transaction is final!

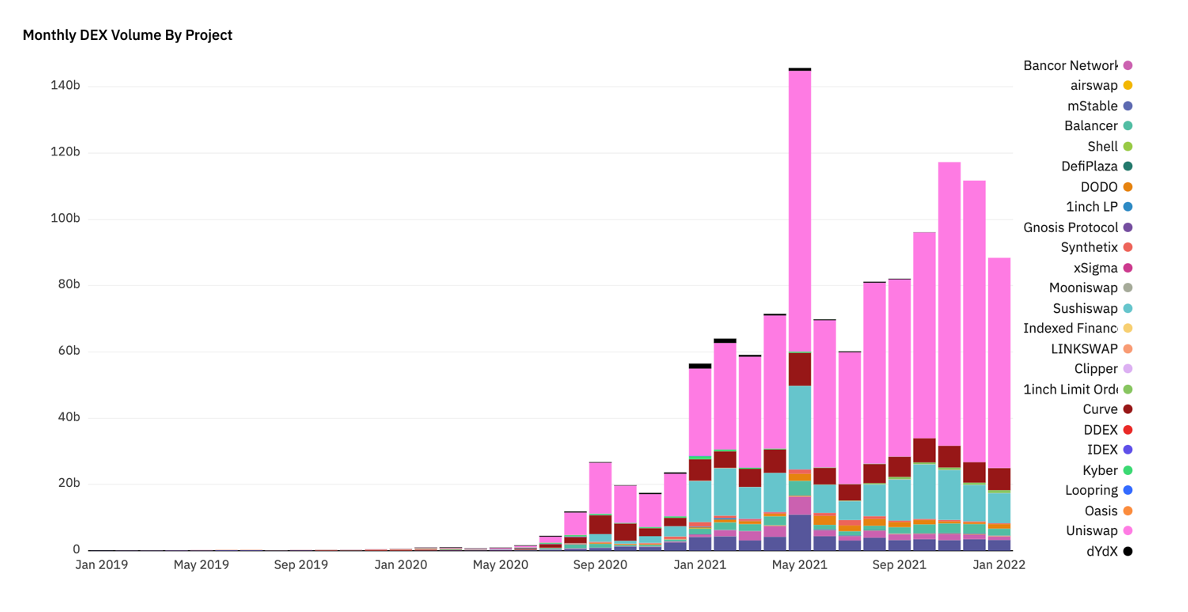

Since DeFi has grown at such an astounding rate, the opportunities for MEV have grown exponentially. We regularly see DEX volume’s surpass $80 billion per month and with the cost of a 1-month Ethereum 51% attack only being $999.86 million (less than 1% of Dec 2021 Dex volume), Time-Bandit attacks represent a very serious threat to the consensus of the chain.

Since the MEV in blocks is extremely large, attackers could potentially use these profits to rent hardware from the cloud in order to perform these quasi 51% attacks. It does seem somewhat unlikely that miners would damage the long-term growth of the network as they have a significant interest in its success, but the incentive do so is present.

If you are interested to learn further, here is a great resource:

https://thedailyape.notion.site/MEV-8713cb4c2df24f8483a02135d657a221What is MEV?

good stuff

Great Read, Keep up the good work .